The Wall

Extract from "From Rock to Kraut" (2008)

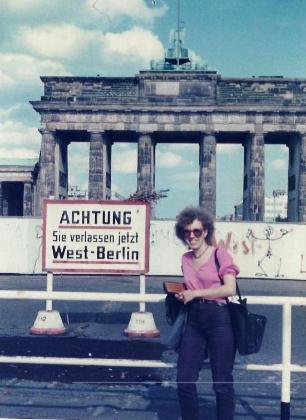

(c) Anli Serfontein. The author in West Berlin in 1985

I was twenty-six when I first visited West Berlin in 1985, and it would be another five years before I visited a united Berlin. In 1985, I travelled by car from West Germany with Su. At the border post in Helmstedt, we were kept for a long time, as my South African passport caused consternation. In those days there was a transit corridor between the border of West Germany and West Berlin, passing through East Germany. The East Germans could control as they wished, but in principle they had to let everyone pass.

That did not prevent them from turning my South African passport upside down. Eventually, we were signalled to proceed and got back into the car, but we still did not have the all clear. As we got to the barrier, the East German border policeman asked Su about me, when I chipped in. His response was, “Ach, Sie sprechen Deutsch— Oh, you speak German!”, and he waved us through. I found that baffling, because the fact that I was a German-speaking South African should have made him suspicious. We drove the two hours to West Berlin on the old Autobahn built by Hitler in the thirties, without being allowed to stop. It was a far cry from the West German Autobahn—here there was a speed limit of hundred kilometres per hour, and the state of the road and the potholes made speeding near impossible. It was a surreal feeling.

Su and I spent a wonderful week in Berlin with her sister, who lived in Wannsee, then literally two kilometres away from the border. When I was filming in Berlin with my Dad in 1998, we were staying in Potsdam in the former East Germany, and we were able to whiz past Wannsee on the Autobahn, barely fifteen minutes away. I found it hard to believe that only a decade before that would have been impossible.

I still have a photo hanging above my desk taken of me in 1985 in front of the Brandenburg Gate and the Wall, with a sign that says, “Achtung Sie verlassen jetzt West-Berlin”—Attention: You Are Now Leaving West Berlin.

A day later, I was standing on the other side of the Brandenburg Gate in East Berlin, after having passed through Checkpoint Charlie and asking them PLEASE not to stamp my South African passport, as I would get into trouble back home. All I remember was how grey and dreary the place was and how we struggled to spend the money we were forced to change; in the end we bought badly bound books and left the rest with a cousin of Su’s. We also visited an art exhibition full of grotesque socialist realism paintings, housed in the beautiful Old Museum.

In the summer of 1990, shortly before re-unification, but a few months after the Wall came down, Louise and I visited her aunt in Berlin, and I insisted on walking through the Brandenburg Gate. Every time I visit Berlin, I am still amazed that I can walk from one side of the Gate to the other with such ease.

On that visit, her aunt and her boyfriend, who was living in Kreuzberg near the old Wall, took us on trips through run-down parts of East Berlin. We spent a morning in a park with the huge socialist realistic busts of the fathers of socialism—Marx, Lenin, Stalin and others. Today that has all disappeared, and it is as if a Socialist State never existed.

I was travelling with a small child and a buggy and had to go up and down stairs to station platforms, sometimes with no escalators or lifts, to travel around Berlin. It was the time of the first summer sales in Berlin for the East Germans. My child and her buggy helped me to determine whether someone came from the West or the East. The Wessis stopped and helped me carry the buggy plus child up the stairs. The Ossis, finally in the West, were rushing past so as not to miss a minute of the sales.

On that visit Su’s sister gave me a piece of the Wall, parts of which were still visible all over the city and which I proudly took back to South Africa. Her sister and her young son had chiselled it away, like everyone in Berlin doing their bit to bring the Wall down. It had a place of honour on my sideboard. I put it on my dining room table with all the other ornaments the removal company had to pack when I left South Africa. It never arrived in Germany, and I can only think that whoever packed it must have thought, “Who is so daft as to pack a piece of brick!” It is a loss I still mourn, knowing how much one pays for a piece of the Wall these days.

Twentieth-century German history can be summed up using the date, November 9. In 1918 it was Armistice Day, ending the First World War started by the Germans. Twenty years later in 1938, it was Kristallnacht, the night during which the Nazis organised a pogrom throughout Germany, burning and destroying synagogues and breaking the windows of Jewish shops and houses; from that point on it was virtually impossible for Jews to earn a living here or to own property. And then the evening of November 9, 1989, when the East German authorities opened the border to the West for the first time in thirty years.

After weeks of protests by the East German people, the Berlin Wall fell peacefully and East and West Germans met freely for the first time in three decades. It signalled the end of the Cold War and all over Eastern Europe democracies were mushrooming.

Today, the euphoria of that autumn night eighteen years ago when the unthinkable became reality, is gone. The hard realities of a unified Germany are clouding people’s assessment of it. Most East Germans still think that it was the greatest event of their lives. The majority believes that it was made possible by the people themselves, who with their poignant slogan “We are the people”, brought down the Communist regime.

But often in my travels in the East I have noticed that the dissatisfaction of East Germans with life after unification crosses political divides. There is still a “them and us” mentality that has taken a long time to subside. Most worry about unemployment, which is highest in the federal states in the East. Other drawbacks are social insecurity; the steadily rising cost of living; and the sharp increase in criminality since unification. Because of conditions in East Germany, people only survived by helping each other and showing solidarity. Many now feel the lack of humanity and solidarity among the people in the East, which, like the West is increasingly becoming a success-orientated, competitive society.

In contrast to my child and buggy experiences in 1990, I enjoy working in the East and have always felt that people have been generally so much more helpful than when filming in the West.

In late October 1999, almost ten years after the fall of the Wall, BBC News contacted me to ask whether I would be able to do some research for them on the fall of the Wall. I was busy celebrating my daughter’s 11th birthday party when the call came. As so often happens with the BBC, things were left way too late, and I had literally five days to try and find the people who correspondent Brian Hanrahan met on the night the Wall fell in 1989.

Brian was in East Germany at the time and heard the Wall was falling via word of mouth. He went to Bornholmer Street. That night it was the first border post to open its barriers to the West. Brian and his camera team were there, going with the flow and talking to Ossis crossing into the West for the first time. Based on his footage, the Germans later made a film, and ten years later I had to find these people on the basis of very skimpy information.

Working for the BBC can be extremely challenging in both a negative and positive way. The Brits have a way of keeping their cool, and nothing is a problem, which does not sit well with a feisty South African. During my research on that film, I came to appreciate where I live. Every so often, when I reached another cul-de-sac in my research, I would go for a quick walk down Tiergarten and through the woods.

For a start, the British, not being the greatest of linguists, made things extremely difficult. So all I was given was a list of people to contact, plus, in some cases, phone numbers from early 1990. Now it may sound as if my colleagues were being incredibly helpful. Well, there were some minor

hiccups to start off with. For example, after unification in 1990, all old East Berlin phone numbers changed. I had also never seen the film and therefore did not know whether the names of the interviewees fitted East or West Germans. So where should I start to look?

Single women may have married in the meantime and changed their names. And some names are very common. There was a certain Susanne Fischer whom they interviewed on that evening, and I counted seventeen Susanne Fischers living in Berlin. I gave up after phoning half of them.

There was a particular waiter who Brian interviewed in a disco on the Kudamm—the famous and fashionable West Berlin shopping street—and who he was keen to have in the film as he was young and from the East. He came from Burg and I was given a number for him. With all East German telephone numbers no longer valid, this turned me into a super sleuth. There are only twenty-seven villages called Burg in Germany. So I required a map to try to work out which ones were in the former East Germany. There were three near enough to Berlin. BBC producer Paul Simpson, looking at the notes and having to deal with my calls of desperation then deciphered “Burg bei Magdeburg”.

Now a young guy like that would have lived with his parents. I was told there was a restaurant in the castle in the village and assumed that he probably worked there. But then the restaurant no longer existed so I called the Tourist Information who passed me onto someone else: I called random people in the village, and it emerged that he had left Burg, like so many young people did after unification, and that he went to the West. Eventually I was given the number of a relative of his, who told me that he had moved to Munich, but was doing a course in Spain at the present time. Ten years after Brian filmed him, I reached him in Spain on his Spanish mobile phone and as fate would have it, he was going to be back in Munich on the weekend we were planning to finish filming. Having gone to such lengths to find him, I never met Marko. On the Sunday Paul and Brian flew down to Munich from Berlin to interview him, while I flew back to Trier, mission accomplished. Of all the sad stories of people who did not adapt to the pace of the West, Marko was one of the success stories, embracing the possibilities the West had to offer.

On October 3, 1990, the two German states that were created at the end of World War Two by the Allies were re-united, to form a united Germany. It was just over ten months after the fall of the Berlin Wall. The two Germanies had one culture and one language, but there the similarities ended. Their post-war history was that of the Cold War. West Germany was a model market economy; East Germany was a model socialist state.

In Johannesburg, Su had a dinner at her place with some Germans; we listened to Deutsche Welle on the radio and at midnight toasted the new German State. In the poignant words of the former mayor of West Berlin, Willy Brandt, now grows together that which belongs together.

Many years previously in Amsterdam I asked a leftie German friend of mine Helmut, what he thought of two Germanies. He replied that every German wanted re-unification. At the time it was a pipe-dream. So now in 1990 the world was changing—in February Mandela was released from prison, something we could not have envisaged in our wildest dreams a decade earlier and a few months later, the two German States were unified.

Fears of a new wave of German nationalism expressed by neighbouring States at the time, and especially by Britain’s Margaret Thatcher, who vehemently opposed unification, have long since been proved unfounded. But with fifteen million more inhabitants, Germany has become the most dominant State in European politics. But it is not only in politics, but with its economy that the united Germany wants to play a leading role in Europe. And as happened with the economic miracle of West Germany after the Second World War, the first years after re-unification have been geared towards the economic betterment of the East, before the stark realities of the costs hit the people by the mid nineties. Most economists today admit that the process has been much more difficult than they ever thought it would be.

From the beginning, unification was dictated by West Germany. The leaders of the 1989 revolt and prominent East German dissidents were overlooked. The Ossis could be in on the discussions, but the goals were set by the West under Helmut Kohl. And the main goal was for East Germany to achieve the living conditions of the western part within a short space of time. It meant a re-organisation of the whole society—its out-dated industry, housing, transport, telecommunications, education—every aspect of life in the East was affected.

For West Germans little changed, although they felt unification in their pockets with higher inflation and the solidarity tax that came off their pay packets every month. For years to come, money from the West will still flow to the East. For years the German media busied themselves with stories like, “Are we one nation?” or “What Ossis and Wessis think of each other.” This questioning only really abated when a woman from the East became Chancellor.

The political agenda set by Kohl following unification also meant that he needed Ministers from the East in his cabinet. The quota of women in his cabinet mostly came from the East, as more women worked there, and one of his first Ministers was Angela Merkel—a token woman from the East.

When Kohl lost the election in 1998, and Wolfgang Schäuble moved from secretary-general to chairman of the party, she filled the vacant position that all the men in the party were avoiding as a poisoned chalice. With West German arrogance I believe they saw giving her the position as an interim solution.

Filming with Brian in Berlin in 1999, we went with the BBC Berlin office one evening to Borchardts, the in restaurant in Berlin. The journalists at the long table in the middle were all comparing their stories and eyeing each other, being possibly the second most self-centred profession after politicians. My eyes were drifting around the restaurant, when I saw Mrs. Angela Merkel sitting at the next table against the wall. It was Friday evening and she was with a man whom I did not know, but their conversation looked more intimate than business-like. Being the inveterate

gossip I am, I was interested in who the man was. It was a year after she had become secretary-general of the CDU and so little was known of her. No one else at our table took any notice of her, as most had flown in from London and possibly did not even know her.

Early in 2000, CDU chairman Schäuble was heavily implicated in the slush fund affair, and I went to a couple of press conferences that in those days were still being held in Bonn. She was at every one of them, and in her quiet, unassuming way she impressed me, as she was so completely different from arrogant politicians. I think all the party machos underestimated her grit completely, and she played with this under-estimation of her abilities. Soon afterwards Schäuble resigned as chairman, and she became party leader, on her way to ultimately becoming Chancellor in 2005.

The man at her

table that evening was her husband, a professor of Chemistry.